** AISHBO = As It Should Have Been Opined

Cite as: 561 U. S. ____ (2010) 1

Opinion of the Court

NOTICE: This opinion is subject to formal revision before publication in the preliminary print of the United States Reports. Readers are requested to notify the Reporter of Decisions, Supreme Court of the United States, Washington, D. C. 20543, of any typographical or other formal errors, in order that corrections may be made before the preliminary print goes to press.

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

No. 08–964

BERNARD L. BILSKI AND RAND A. WARSAW,

PETITIONERS v. DAVID J. KAPPOS, UNDER

SECRETARY OF COMMERCE FOR INTEL-

LECTUAL PROPERTY AND DIRECTOR,

PATENT AND TRADEMARK OFFICE

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF

APPEALS FOR THE FEDERAL CIRCUIT

[June 28, 2010]

JUSTICE Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. delivered the opinion of the Court. (Joining with him are: JUSTICES Felix Frankfurter, ... and ...) ... [write up still a work in progress ]

This Court's usual modus operendi is that of seeking out a single question of law upon which to cast our focus and then of providing clarifying guidance thereon.

Regrettably, in this particularly complex patent case, we find ourselves grappling with numerous and interlocked parallel issues, including:

(1) Is there a limit of scope to the term "process" as used in patent law section 35 USC 101 and if so how is the boundary line therefor to be defined?

(2) What procedural process is due for determining what "the invention" is, what its scope is and whether that scope exceeds the boundary line defined under the first question?

(3) For each specific patent claim presented below by Petitioners Bilski and Ward, have the adjudicative bodies below employed a legally appropriate test and procedure such that Petitioners Bilski and Ward may be said to have received due process?

SECTION I: STATUTORY CONSTRUCTION

In search for an answer to the first question (1) we invoke basic canons of statutory construction, our long recognized doctrine of judicial restraint and a check for conflict with other Constitutional provisions (e.g., First Amendment).

With regard to textual analysis of 35 USC 101 itself, there is no rational basis for debating existence of numerous unequivocal words within the express language of 35 USC 101. The term "any" has long been recognized as being extremely broad:

[101 Title:] Inventions patentable.

Whoever invents or discovers

any new and useful

process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter,

or any new and useful improvement thereof,

may obtain a patent therefor,

subject to the conditions and requirements of this title.

|

"Process" is an independent and first recited one of four statutorily expressed and co-equal categories. To say otherwise, as attempted by the court below (with the so-called "Machine or Transformation Test", hereafter "MOT Test"), would render as surplus, the terms "process" and "any" in contravention to canons of statutory construction.

It very well may be true that essentially all machines are "manufactures" and they are entirely composed of "compositions of matter". Nonetheless, a claim for an invented "machine" need not recite the specific materials of which the machine is composed nor the shapes and precise dimensions of every article of manufacture that may operate as a functional part in the machine. Thus the invention of a "machine" may be separated from the invention of a "compositions of matter" and invention of a "manufacture".

We are not prepared to say here whether all "manufactures" must be compositions of matter or what textbook of alchemy provides the ultimate Gospel line dividing between matter and non-matter. Those question have not been adjudicated below and judicial restraint mandates that we not pass on such unripe questions here. Theories about the nature of mass, matter and gravity are fabricated by fallible men and oft prove to be short sighted.

We note however, that since there is no need for the second spoken-of "machine" in 35 USC 101 to be specifically tied to another statutory class, the well worn adage about gravy for the goose and sauce for the gander applies to "process".

Process is at least co-equal to machine in the text of 101 if not its superior by virtue of having a term expanding definition in 100(b){reproduced below}. Accordingly, there is no basis for requiring a "process" to be tied to a particular machine or to a specified transformed composition when no such noose hangs about the neck of machine.

Just as a given "machine" may be used for providing new and improved methods not originally contemplated by claim language defining the original machine structure, so too a given "process" may be carried out in improved form by apparatus not originally contemplated by the claim language for the original method. 35 USC 101 mandates this outcome by its language, "or any new and useful improvement thereof".

Because of the symmetric mirror relationship between "machine" and "process", the so-called MOT Test which was invented below simply to support a pre-conceived conclusion cannot stand as the ultimate and exclusive definition of what constitutes any "new and useful" process. Only Congress can add limitations to what otherwise is "any" new and useful "process".

With regard to the term "process" as well as "invention", there is no foundation for asserting that Congress has not broadly defined the terms, "process" and "invention" in 35 USC 100(b), Congress has not left open a door of ambiguity beckoning us to trespass there into by way of activist judicial intervention:

[100 Title:] Definitions.

When used in this title unless the context otherwise indicates -

(a) The term "invention" means invention or discovery.

(b) The term "process" means process, art, or method, and includes a new use of a known process, machine, manufacture, composition of matter, or material.

|

Indeed if we were to substitute into 101 the definition provided by 100(b) the result would be the following:

[101 Title:] Inventions patentable.

Whoever invents or discovers

any new and useful

[process, art, or method, [or that which] includes a new use of a known process, machine, manufacture, composition of matter, or material] ...

or any new and useful improvement thereof,

may obtain a patent therefor,

subject to the conditions and requirements of this title.

|

Moreover, there is no denying that Congress has recognized the option available to inventors to file for so-called "business methods" as evidenced by 35 USC 273:

[273 Title:] Defense to infringement based on earlier inventor

(a) DEFINITIONS.- For purposes of this section-

[(a)](3) the term "method" means a method of doing or conducting business;

(b) DEFENSE TO INFRINGEMENT.-

(1) IN GENERAL.- It shall be a defense to an action for infringement under section 271 of this title with respect to any subject matter that would otherwise infringe one or more claims for a method [as defined above] in the [lawfully issued] patent being asserted against a person, if such person had, acting in good faith, actually reduced the [business method] subject matter to practice at least 1 year before the effective filing date of such [lawfully issued]patent, and commercially used the subject matter before the effective filing date of such patent. [(textual material in brackets added here)]

|

Additionally, Congress has expressed recognition in 35 USC 102 of the natural ability and right of any inventor and with respect to "their" private property to conceal it from the public:

[102 Title:] Conditions for patentability; novelty and loss of right to patent

(g)(1) ... the invention [that previously] was made by such other inventor and not abandoned, suppressed, or concealed [as is a natural right of such other inventor] --emphasis and clarifying text added

|

The dissent asks us to turn a blind eye to all of these clear enunciations of Congress and to instead engage in judicial activism and to legislate from the bench new rules of patent eligibility in contravention to the spelled out intent of Congress.

Starting with the 1952 Patent Act and through 58 years of follow on legislation, Congress has made it clear that an invention firstly is the private property of its creator.

Congress has also indicated that the act of defining that which is to be regraded as "his invention" (see 112 below) is in the hands of its creator. Definition of "the invention" is particularly set forth in the claims. The latter are construed in light of the inventor-authored specification from which such claims spring forth as an integrally attached part of the specification.

To ignore all this would violate fundamental tenants of separation of power, would upset our long standing doctrine of judicial restraint and would lead to absurd and inconsistent interpretations of statutory language.

The dissent asks us to blur our eyes and to not carefully examine all the words in each claim presented by Bilski and Warsaw but to instead merely pass on the claims as being "abstract". This too is in contravention to the spelled out intent of Congress whereby the scope of exclusivity granted under a patent is defined pursuant to 35 USC 112:

[112 Title:] SPECIFICATION

The specification shall contain

a written description of the invention,

and of the manner and process of making and using it,

in such full, clear, concise, and exact terms as to enable any person skilled in the art to which it pertains, or with which it is most nearly connected,

to make and use the same, and shall set forth the best mode contemplated by the inventor of carrying out his invention.

The specification shall conclude with one or more claims

particularly pointing out and distinctly claiming

the subject matter which the applicant regards as his invention.

|

SECTION II: Are there subject areas which are not patent eligible?

Invention in its broadest sense is not anything new under the sun. All persons of competence "invent" on a fairly routine basis. The question is what do they invent, in what subject area? Is their invention a tall tale, or a creative excuse for why they don't have their homework or is it something more useful?

This Court has held in KSR v. Teleflex that there are many inventions which are merely routine outcomes of ordinary market forces and ordinary creativity as well as of common sense and thus do not rise to a level of contribution to the general welfare so as to justify grant of a patent. While that observation comes under the rubric of 35 USC 103 and not 101, it would be hypocritical of us to now say that the act of inventing per se is not an ordinary and routine process (a way of doing something) but rather some mysterious craft whose abstractness can only be understood by a sorcerer and one or two trusted apprentices.

Even at the time of framing of the U.S. Constitution there was no shortage in inventiveness by persons who were fond of telling folktales (e.g., Chaucer's The Canterbury Tales)and contriving all manner of theories (e.g. Lamarck's theory of evolution) and other amusements.

However the Framers observed that there was a particular kind of inventiveness and creativity that was in extreme short supply. This was in a domain that they referred to as the "useful arts". Accordingly, and in spite of their strong abhorrence to granting of monopolies in any manner of endeavor, they nonetheless went out of their way to inscribe into the original U.S. Constitution, in Article I, section 8, clause 8 thereof, the following empowerment:

[Article I, Section 8, clause 8:]

The Congress shall have Power ... To promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries.

|

Legal scholars recognize that the phrase, "To promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts" is but one of many possible reasons that Congress may have for securing to creative persons (authors for example), exclusive rights to their respective works of creativity (works of creative authorship for example). There is no pretense in the U.S. Copyright laws of their existence being justified only for the sake of promoting the progress of science and useful arts. Copyright is available for all affixed and originally authored works of expression that have a modicum of creativity and remain on the non-abstract side of the idea/expression divide. ***

Instead the legislative recognition is that of initial ownership by the creator of his or her work of authorship or inventorship. The creator and exclusive owner of such work is free to destroy such work upon its creation or to suppress and conceal it at his or her whim dictates. An invented creation does not become a ward of the commons at the moment of its conception. This is a fundamental aspect of ownership in personal property. The invention is owned by its creator. Article I, section 8, clause 8 implies essentially this when referring to "their respective Writings and Discoveries". It belongs to them as a matter of natural rights and Constitutional recognition.

A foundational purpose of our U.S. Copyright and Patent laws is to promote the general welfare by encouraging creators of certain kinds of work to share knowledge of their work with the public rather than keeping the same as a trade or other secret even though the latter is equally their right.

With these foundations having been laid out, it is nonetheless also a tenet of our free society that "ideas", once they are released into the public domain as such, should be free to take flight and spread their wings amongst all people so as to be fully debated and appreciated while they retain their essence of being merely abstract ideas.

Freedom of expression of ideas is made sacrosanct in the First Amendment of our Constitution:

|

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.

|

Free speech and freedom of press cannot exist without freedom of thought and freedom to express one's abstract ideas (within limits; such as not falsely shouting "fire" in a crowded theater). Some may argue that freedom of religion also involves the expression of abstract ideas. However such a question is outside of our ambit of judicial review.

SECTION II(a): Abstract Ideas in Detail

We have already outlined in Diamond v. Diehr that a patent claim may not wholly preempt communication of "abstract ideas". More to the point, the claims in Diehr included recitation of a mathematical model that was believed then to be an adequate modeling of what occurs in a rubber curing process. ... still under construction

The proceedings below can be characterized as a failure to treat Messieurs Bilski and Ward with dignity deserved by all human beings. Instead there is a cacophony of cat calls and a flailing of the bull's horn in the china shop. To mock men who may be trying to bring forth a new and useful process to the attention of the public is beneath us. We do not here pass on ancillary questions such as whether the claims at bar suffer from over-breadth, but certainly they do not literally preempt any communications about the "idea" of hedging. To infringe on Claim 1 of the Bilski application; which claim has not even issued and could have been amended in prosecution, one must initiate ... Even if done with nothing more than a set of telephone calls, the making of a telephone call is not an abstract step but rather a physical one that deserves recognition for what it truly is. ...

there is still the issue of an

idea/expression dichotomy in Copyright law and of an idea versus practical-utility and implementation dichotomy in Patent law. ...

... still under construction

An ancillary question is whether Petitioners Bilski and Warsaw have contributed inventively to the useful arts under terms of 35 USC 101 by being apparently first to disclose and claim a process that is particularly pointed out by claims they have lawfully filed pursuant to 35 USC 111 with the USPTO (United States Patent and Trademark Office, an Administrative Agency within the Department of Commerce).

place each one outside the 3 point basketball circle

relative to the elephant and put a Geiger counter or compass in the hand of

each blind Justice whereby each senses the “spin” around the Bilski claims but none of them actually touches and “gets

it” directly (by hand or even with a blind man's walking stick).

place each one outside the 3 point basketball circle

relative to the elephant and put a Geiger counter or compass in the hand of

each blind Justice whereby each senses the “spin” around the Bilski claims but none of them actually touches and “gets

it” directly (by hand or even with a blind man's walking stick). In this hypothesized cartoon, one Justice would be saying, “My Geiger counter says it ‘feels’

that the Bilski elephant is too “abstract”. I say the physical steps in Bilski

were never there to begin with and certainly I don’t see them.”

In this hypothesized cartoon, one Justice would be saying, “My Geiger counter says it ‘feels’

that the Bilski elephant is too “abstract”. I say the physical steps in Bilski

were never there to begin with and certainly I don’t see them.”  Another would say, “My sundial is

foreshadowed by an ancient sun and indicates that the Founding Fathers would have frowned on this sort of progress.

The business of patents is not business –irrespective of whatever the word

“business” might mean”.

Another would say, “My sundial is

foreshadowed by an ancient sun and indicates that the Founding Fathers would have frowned on this sort of progress.

The business of patents is not business –irrespective of whatever the word

“business” might mean”.  A third would

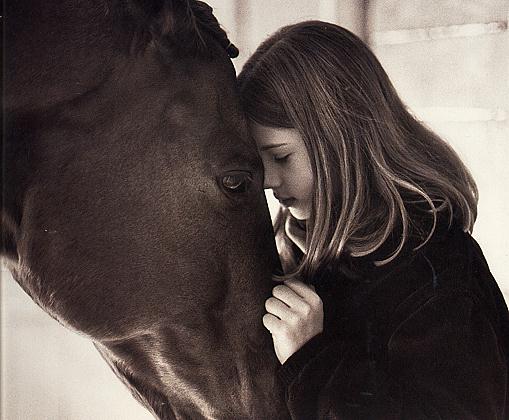

say, “My MRI spin machine indicates this creature is an "information" provider like a teacher or a trainer, for example a horse whisperer

or an antitrust law lecturer and therefore the creature “explains” the abstract

conceptualizations revolving around the hedging thing and nothing more substantive than that.”

A third would

say, “My MRI spin machine indicates this creature is an "information" provider like a teacher or a trainer, for example a horse whisperer

or an antitrust law lecturer and therefore the creature “explains” the abstract

conceptualizations revolving around the hedging thing and nothing more substantive than that.”